CW3E Publication Notice

Are AI weather models learning atmospheric physics? A sensitivity analysis of cyclone Xynthia

March 20, 2025

Scientists from the CW3E machine learning team recently published an article titled “Are AI weather models learning atmospheric physics? A sensitivity analysis of cyclone Xynthia” in npj Climate and Atmospheric Science. This study was led by Jorge Baño-Medina (CW3E) and co-authored by Agniv Sengupta (CW3E), James D. Doyle (U.S. Naval Research Laboratory), and Carolyn A. Reynolds (U.S. Naval Research Laboratory), Duncan Watson-Parris (SIO), and Luca Delle Monache (CW3E). This work aligns with CW3E’s goal to develop and leverage emerging artificial intelligence (AI) technologies to improve the prediction and advance our understanding of extreme weather events. The work was supported by the Office of Naval Research (ONR), California Department of Water Resources’ AR Program, and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ Forecast Informed Reservoir Operations.

The central research question of this study is: Are Artificial Intelligence (AI) weather models learning atmospheric physics? Addressing this question is crucial to understanding how these models work and increasing our trust in their estimates. These tools can then be applied with confidence for the prediction of (extreme) weather, as well as for observation network design, probabilistic forecasting, and the study of atmospheric dynamics.

This study presents an innovative methodology to study the sensitivity of forecasts to initial condition uncertainty through AI global weather models, which have recently shown remarkable forecasting skill, rivaling traditional physics-based systems, while offering the advantage of much lower computational real-time demands (on the order of seconds vs hours). These models, typically trained to forecast weather up to 6 hours ahead, can also produce longer forecasts through auto-regression. The study focuses on Cyclone Xynthia (02/2010), an extreme weather event in Western Europe that resulted in significant casualties and damages estimated at several millions of dollars. Gradients of kinetic energy at 36 hours lead time with respect to atmospheric features at the initial time—commonly referred to as sensitivities—were computed leveraging the backpropagation algorithm of the AI model. To understand how well the AI model has learned the physical relationships between different variables, we use physics-based sensitivities derived from an adjoint model as a reference for comparison.

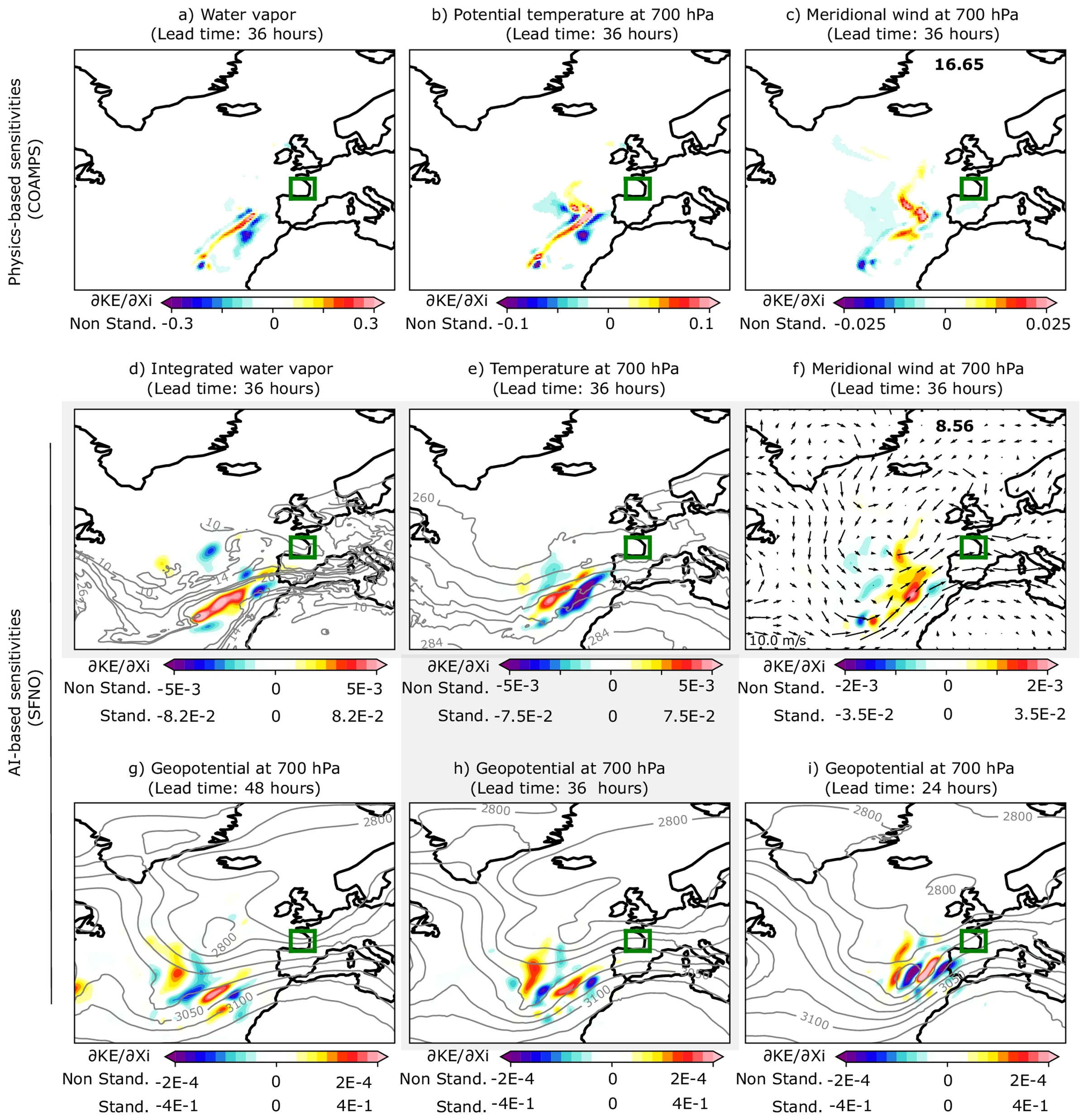

The results indicate that the AI-based sensitivities exhibit spatio-temporal patterns that are consistent with those from physics-based models (see Figure 1). Moreover, when perturbations based on these sensitivities are scaled according to estimates of initial condition uncertainty, the AI-derived response closely resembles that of the physics-based model.

These findings are significant because they demonstrate that AI weather models are not only capable of producing accurate forecasts very quickly but also of learning consistent spatio-temporal atmospheric links in the atmosphere. This has important practical implications for weather services, which traditionally rely on computationally intensive physical models to understand the weather patterns that lead to extreme events. The AI-based methodology presented here could complement or, in some cases, replace these costly physical models, enabling the rapid computation of sensitivities in a fraction of the time and with minimal computational resources. This increased efficiency could enhance our ability to forecast extreme weather events in real-time by generating large ensembles based on these sensitivities to better represent the tail of the distribution. These tools will also allow services to deploy observations in the identified sensitive areas, such as during the Atmospheric River Reconnaissance campaign (Ralph et al., 2020), a project endorsed by the World Weather Research Program (WWRP) for flight-track planning, to improve the initialization of the forecast. They will also be used to improve our understanding of the underlying physical processes.

Figure 1. Physics-based sensitivity fields of the kinetic energy over the Bay of Biscay (green box) at 36 hours of lead time for a) water vapor, b) 700-hPa potential temperature, and c) 700-hPa meridional wind, as computed in D14. AI-based sensitivities of the kinetic energy for d) integrated water vapor, e) 700-hPa air temperature, and c) 7-hPa meridional wind. The bottom row shows the 700-hPa geopotential sensitivity fields at g) 48 hours, h) 36 hours, and i) 24 hours of lead time. Contours in panel d), show the total column water vapor from 10 to 30 every 4 kg/m2 at initial time, February 26th 12 UTC. Similarly, in panel e) the contours show the values of temperature every 4K, while in panels g), h), and i), the 700-hPa geopotential is displayed every 50 m2/s2 from 2800 to 3200. Vectors are used to represent the wind intensity at 700 hPa in panel f). Gray shading indicates the panels representing the AI-based sensitivities at 36 hours of forecast lead time. The sensitivities are represented with color bars with different scales to visualize the spatial structures found across variables.

Baño-Medina, J., Sengupta, A., Doyle, J. D., Reynolds, C. A., Watson-Parris, D., & Delle Monache, L. (2025). Are AI weather models learning atmospheric physics? A sensitivity analysis of cyclone Xynthia. npj Climate and Atmospheric Science, 8(1), 92, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-00949-6

Ralph, F. M., Cannon, F., Tallapragada, V., Davis, C. A., Doyle, J. D., Pappenberger, F., Subramanian, A., Wilson, A. M., Lavers, D. A., Reynolds, C. A., Haase, J. S., Centurioni, L., Ingleby, B., Rutz, J. J., Cordeira, J. M., Zheng, M., Hecht, C., Kawzenuk, B., & Monache, L. D. (2020). West Coast Forecast Challenges and Development of Atmospheric River Reconnaissance. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 101(8), E1357-E1377. https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-19-0183.1